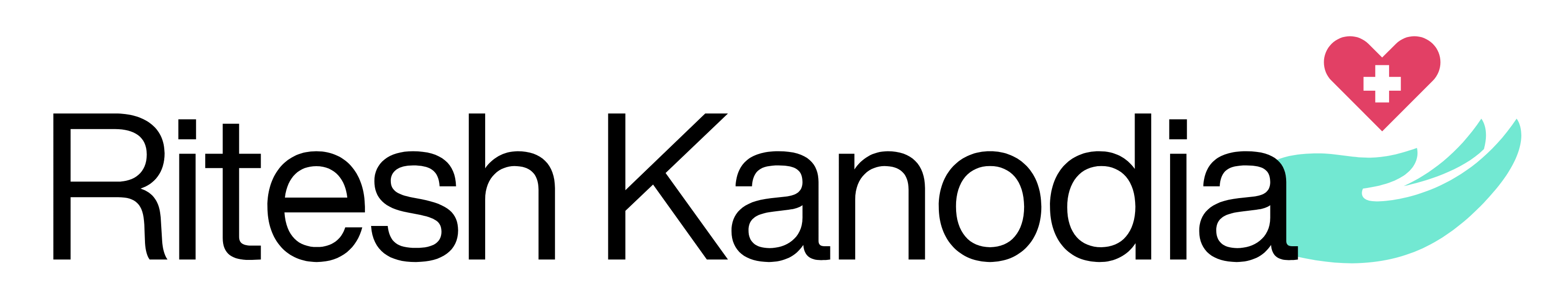

Drainage

What is image-guided percutaneous drainage?

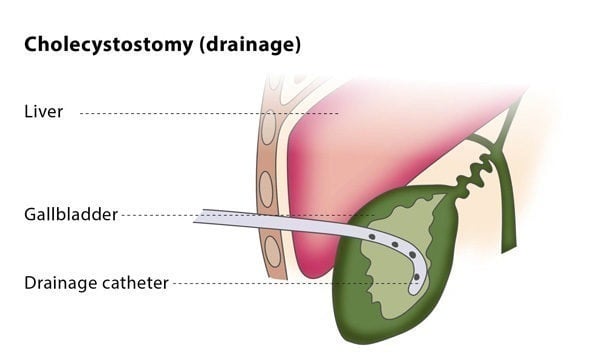

Image-guided percutaneous drainage involves using a catheter (a thin tube) to drain an abscess or a collection of fluid or air under image guidance. The interventional radiologist will insert a flexible catheter through a small cut in your skin and will guide the catheter to the collection of fluid or air. The fluid or air will then be collected in a drainage bag.

Drainage catheters are available in a variety of sizes, shapes and types. The interventional radiologist will choose the catheter according to the type of fluid, along with other factors.

How does the procedure work?

If you are on any medication that prevents blood clotting, you will stop taking it before the procedure, if possible.

You should not eat anything for at least four hours before the procedure starts. You may be asked to fast for longer, depending on the puncture and difficulty of your particular case. Before the procedure, the interventional radiologist will usually place a needle in your vein to make access easier during the procedure.

Why perform it?

Percutaneous drainage is recommended to treat fluid or air collections which produce symptoms (such as pneumothorax, which is the collection of air or gas in the gap between the chest wall and the lungs). It can also treat recurrent fluid collections by using medication and is a minimally invasive method of draining abscesses.

This procedure may not be suitable for you if you suffer from a blood clotting disorder or if the interventional radiologist cannot find a safe access route for the catheter.

The percutaneous drainage procedure cures infected fluid/air collections in over 80% of patients, though failure occurs in 5-10% of patients.

Because of the wide range of types of uninfected collections, the success rate of drainage for uninfected collections is highly variable.

What are the risks?

There are some risks associated with the procedure. Major complications include bacteraemia (the presence of bacteria in the blood, which occurs in 2-5% of cases) and septic shock (caused by severe infection and sepsis, which occurs in 1-2% of cases). Other complications include the risk of haemorrhage and superinfection (infection of a sterile collection of fluid, following a previous infection).